AN INTRODUCTION TO ROTATION 2 IN VOLLEYBALL

In the second of our 6-part volleyball rotations and overlap series, we are exploring rotation 2 in volleyball. Due to the overlap rules in volleyball, rotation 2 has far fewer options than rotation 1.

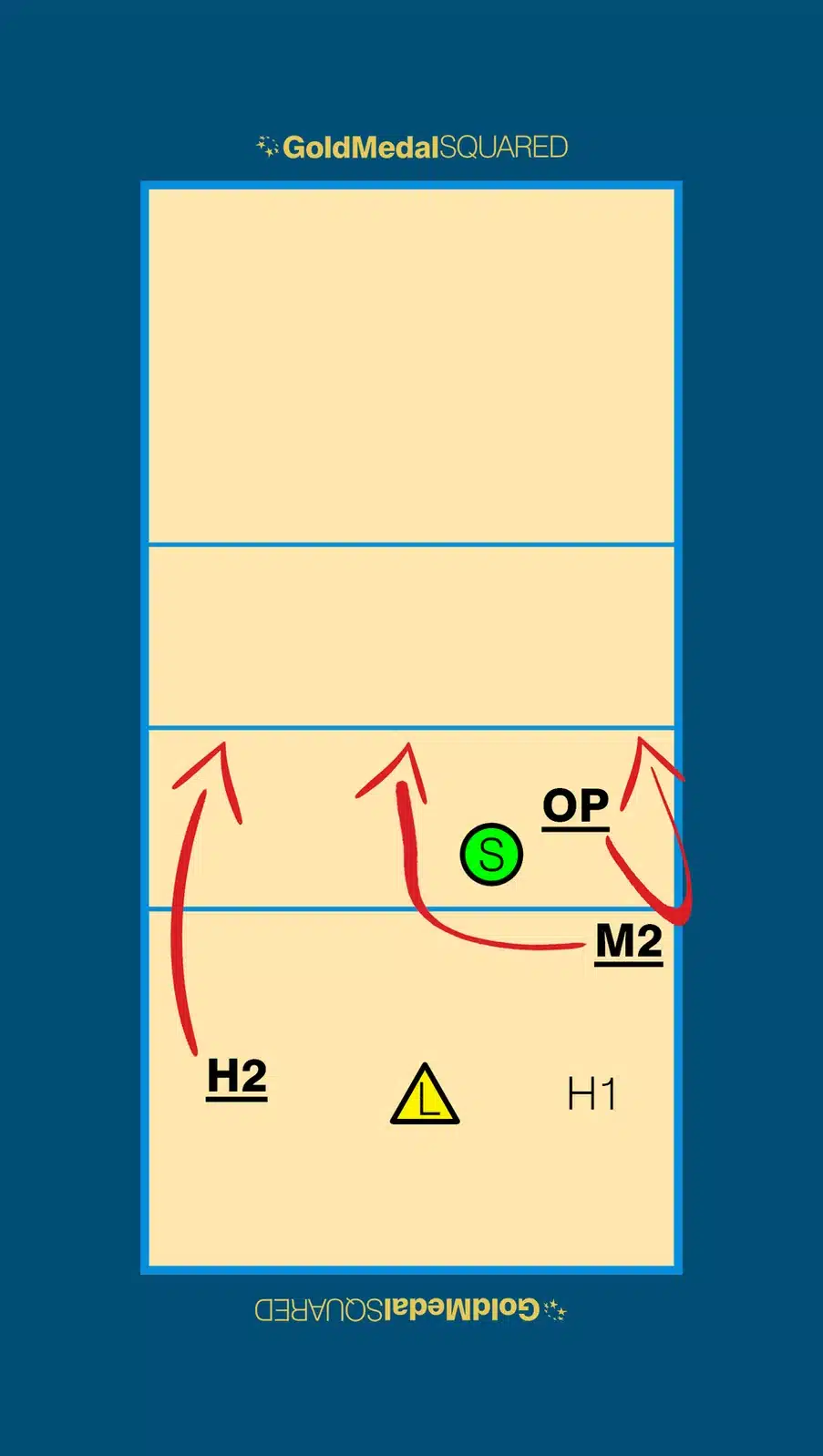

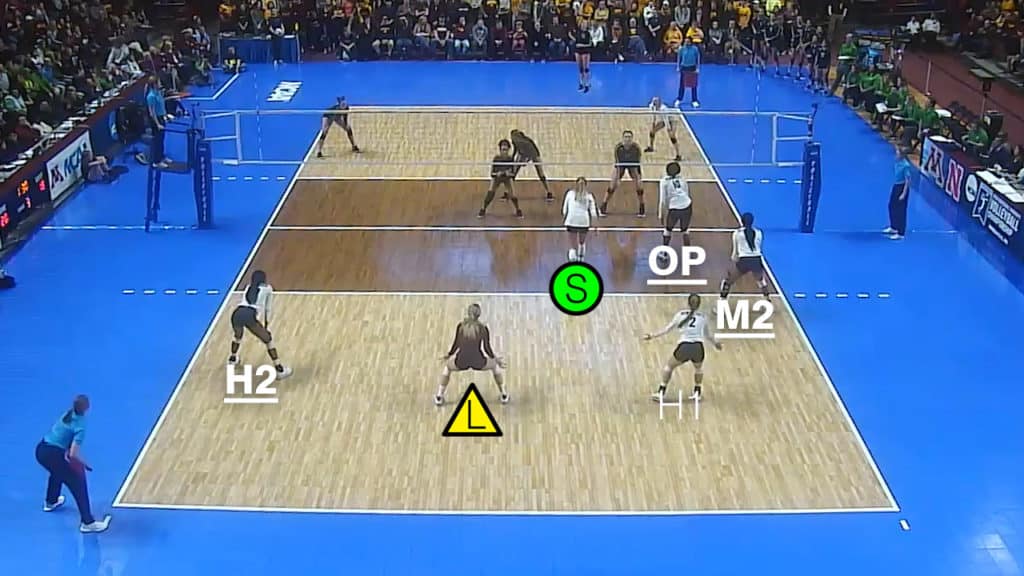

The players have rotated one position clockwise around the court. Here is where they are in Rotation 2.

Bold & Underlined Text = Front Row Players

In Rotation 2, the H1 is in Zone 1, followed by the M2, Opposite, H2, M1 (replaced by the libero) and finally the Setter. In Serve-Receive, there is only one commonly used formation.

ROTATION 2 – Traditional Serve-Receive Option

Player Assignments by Position:

S: Starts in Zone 1 behind the H1

H1: Passes in Zone 1

M2: Starts in Zone 2 and hits Quicks

OP: Starts in Zone 2 in front of the Setter and hits Reds

H2: Passes in Zone 5 and hits Gos

L: Passes in Zone 6

Advantages/Benefits:

- The three primary passers are passing with the Libero in the middle of the court.

- The Setter is allowed to start the rally already in the passing zone.

- The attack approaches are simple for all three front row attackers.

- The offensive footwork for the M2 is pretty simple. Watch the “MB Footwork in S/R – Ro 1,2,3” video on GMS+.

Disadvantages/Drawbacks:

- There is not room for any flexibility here with where each player starts. Each player is essentially locked in to these spots.

Important Overlap Rules Considerations:

- The passing H2 must be in front of the Libero, even though they are both passing right next to each other.

- The Setter must be behind the Opposite.

- The M2 must be to the right of the Opposite.

- The Libero must be to the left of the Setter.

- The H1 must be to the right of the Setter.

Rotation 2 with the H2 Passing in Zone 5 and hitting a go. The OP hits a red. The M2 hits a quick.

Posts in this Series